You may have heard of diastasis rectus abdominis (DRA) because it has been getting a lot of press in the past couple of years. In fact, the Today Show highlighted it in a special Modern Motherhood video: “What Really Happens to Your Pelvic Floor:”

My pelvic health physical therapy colleagues and I are seeing more self-referred postpartum patients because of this increased awareness.

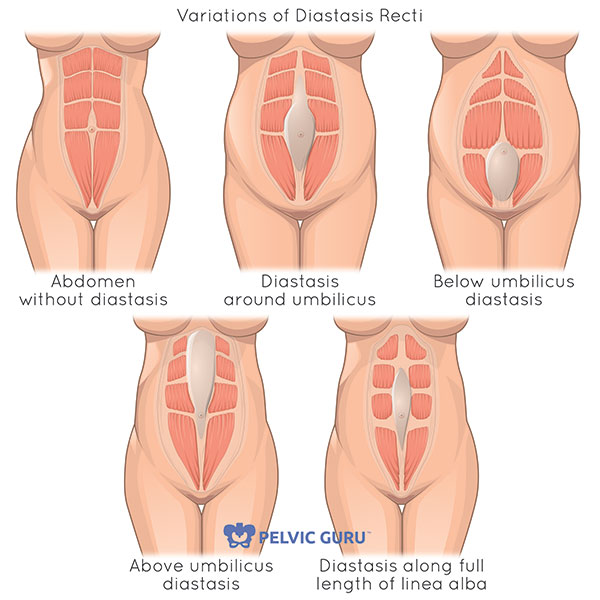

Diastasis rectus abdominis occurs when the normal distance between the two sides of the rectus abdominis, or “6-pack muscle,” widens. Women may notice it’s more difficult to get out of bed and notice “tenting” of the abdomen.

The distance between the the right and left sides of the rectus abdominis isn’t the only aspect of diastasis recti abdominis we evaluate. We also want to note if the fascial integrity at the linea alba is compromised. When you have a baby, your pressure systems in the abdomen change immediately and you can’t find where your center is. Your core control has been shifted completely.

Diastasis rectus abdominis can occur:

- during pregnancy

- after abdominal surgery

- in children before they gain abdominal wall strength; it may remain through the lifetime

- in men too!

Image courtesy of Pelvic Guru

How do I know if I have a diastasis rectus abdominis?

Oftentimes the women I see in the clinic seek treatment because

- they have felt a gap

- their midwife has tested them for diastasis

- their core feels weak

- they are frustrated that their belly doesn’t look the way it did pre-pregnancy

- they have an abdominal bulge that they notice when getting out of bed or during exercise

What exactly is diastasis rectus abdominis?

As physical therapists, we look at a two things: what’s happening at your linea alba and how is force transmitted through your pelvic girdle.

Linea alba

The linea alba is a fascial band between the two sides of the rectus abdominals or “6-pack muscle.”

During pregnancy (and sometimes after) you will see the linea alba widen and the two sides of the rectus pull away from your midline. As physical therapists, we look at the full length of the rectus distance (the “gap”) from the ribs at the top to the pubic bone at the bottom of the abdomen.

To test the gap, we look at the distance between the right and left rectus bellies during a crunch sit-up. Can we pull them wider apart with gentle pressure? What happens when we pre-engage transverse abdominals?

Recent research shows that even though the distance between the rectus bellies might widen with a curl up, the distortion at the linea alba might improve because of activation of the transverse abdominal muscles.

Therefore, when we look at rehabbing someone with a diastasis rectus abdominis, we take into consideration both the gap as well as the fascial integrity of the linea alba.

We evaluate the ability of the tissue at the linea alba to generate force tension, which is accomplished if there is good fascial integrity by noting how easy it is to press into midline and if there is tension underneath our fingers.

Diastasis rectus abdominis aside, we also want to make sure you are able to optimally transfer load through your ribs, abdomen and pelvis.

Common compensatory patterns during load transfer may include puffing your abdomen up or holding your breath. This is important because we want our deepest stabilizing muscles to be in charge of the load for optimal core strength.

Transmitting load through your pelvic girdle

Women often are disappointed or suffer from embarrassment postpartum because they have looser skin, tenting down the center line, and might even be asked by people if they are pregnant.

Beyond how you feel about the way your belly looks, does it matter?

Physically, yes. Our abdominal wall is critical in transferring load across the center of our body. Strength in this part of our core helps prevent back pain, hip pain, and incontinence.

We want our abdominal wall to be as strong as possible, throughout the entire lifespan.

How does an optimal abdominal wall function?

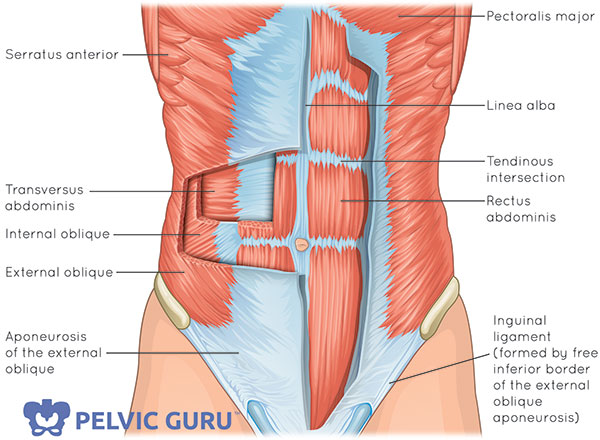

We have four different abdominal muscle groups:

- Rectus abdominis

- External oblique

- Internal oblique

- Transversus abdominis

Image courtesy of Pelvic Guru

In general, including at the abdomen, our deep muscles stabilize us and our superficial muscles (closer to the skin) move us.

The superficial muscles of the abdomen are the external obliques, internal obliques and rectus abdominus muscles. These muscles are responsible for flexing and rotating the trunk.

The deepest layer closest to the abdominal organs is the transverse abdominals (TrA). Your TrA start in your back at the thoracolumbar fascia and wrap around to the front of your body, underneath the linea alba. They stabilize the back and pelvis as well as compressing the lower abdomen and narrowing the waist.

While sometimes we cue “pull in your lower abdominals,” the transverse abdominals extend up to the ribs and down to the hip crest. So, to be accurate, we are focusing on the lower aspect of the belly so that we don’t overuse the obliques.

The TrA, at the abdomen, along with three other deep muscle groups, create an abdominal “canister” of stability:

- transverse abdominals in the front

- multifidi in the back

- diaphragm on the top

- pelvic floor muscles on the bottom

Our diaphragm expands much like how jellyfish move through the water

As you have read in previous blogs, this is what happens naturally when you inhale as seen on MRI:

- diaphragm descends, shortening it’s muscle fibers

- pelvic floor muscles descend in response to intra-abdominal pressure

- transverse abdominals lengthen as the belly expands

What do all of these muscles have in common? They all will “pre-fire” in anticipation of movement.

The second I think about extending my arm to grab a book, my diaphragm, the transverse abdominals, and pelvic floor muscles will be ready to stabilize my trunk. So incredibly supportive and functional!

Which exercises are safe for you?

If you do not have access to a physical therapist trained in abdominal wall evaluation (and pelvic floor to give a complete picture!), you can assess if your exercise program is at a good level for you.

Ideally, your musculoskeletal system will be able to handle the load of the exercise. If the load is too much, you may notice:

- puffing up of the abdomen

- breath holding

- tilting of the pelvis

- bulging at the linea alba

Monitor if you are using the above strategies to decide if your exercise is a good choice for you.

Modification example: Dead Bug

(*This is one example and not a protocol for DRA. Like all musculoskeletal conditions, we want to evaluate the entire person and balance out all the muscles. For example, a full rehab program would include back, abdominal, pelvic floor muscle and hip strengthening exercises along with coordination and balance training. This is simply an example of how one would modify an exercise.*)

An exercise that is frequently prescribed for core stability and seen in exercise class is Dead Bug (both knees and hips are bent at 90 degrees and alternate toe tap down).

If you don’t have enough core control in your system, you might puff the abdomen or notice other compensatory patterns.

Here is an exercise flow that works up to Dead Bug by breaking down the exercise into smaller steps:

Transverse abdominals with pelvic floor muscle contractions

Lay on your back with your knees bent and feet flat. Exhale, zipping up the pelvic floor muscles and transverse abdominals.

Transverse abdominals with bent knee fall out

Lay on your back with your knees bent, feet flat, and TrA engaged. Keep your pelvis still as you allow your right knee to fall to the right then return. Repeat on the other side.

Transverse abdominals with heel lift

Lay on your back with your knees bent and feet flat. Zip up the pelvic floor muscles and TrA hold while you lift you right heel, replace it, lift your left heel, and replace it.

Transverse abdominals with march

Lay on your back with your knees bent and feet flat. Zip up the pelvic floor muscles and TrA hold while you lift your right foot, replace it, lift your left foot, and replace it.

Transverse abdominals with unilateral heel lift with other leg at 90°

Lay on your back with your knees bent and feet flat. Pull the lower abdomen towards the spine. Lift your right leg so that your hip and knee are at 90 degrees. Lift your left heel up and down. Repeat on the other side.

Unilateral brace

Bring one hip, knee and ankle at 90 degrees. Press into opposite hand into your thigh and thigh back into your hand.

Bilateral brace

Bring both hips, knees and ankles at 90 degrees. Press into opposite hands into your thighs and thighs back into your hand.

What about a yoga practice?

As mentioned above, you want to match the load to what your system can handle.

Optimizing Bladder Control: Strengthening the Pelvic Floor is designed to offer gentle loading to the pelvic floor and rest of the core. This video can be a useful home program to have as you work on regaining function and gentle loading of the abdominal wall.

Want more resources?

Diane Lee has done some robust research and teaching in this area and I was fortunate enough to take her course at the International Pelvic Pain Society meeting a few years ago. Check out her online course and book offerings, as well as the numerous journal articles she has published.

Did you find this post helpful? Have you tried something that worked for you and want to share with the Your Pace Yoga community? Let me know in the comments below.

Excellent blog post with very clear pictures! Thank you for sharing!

Thanks so much! Means a lot coming from a colleague!

[…] like you would monitor when exercising with diastasis recti abdominus, you want to be sure that the load is not too much for the system. Be sure you are not bearing down […]

going to send this to my daughter who is due in February,

hopefully, this won’t overwhelm her!

you’re the best!

Aw! So wonderful! It’s good for women to be educated that we don’t just automatically magically bounce back after pregnancy and there are lots of ways we can help ourselves get our center back. Wishing her all the best!!

[…] if you can lift one foot at a time. Be sure to keep the abdomen down towards the spine and not puffing up towards the […]

[…] wall muscles have been stretched out and potentially there is a diastasis recti abdominus (check out this blog on DRA). With all of these changes, how can you set yourself up for […]

fabulous post. Thank you for sharing.

So glad you found it helpful Kim!

I cannot recommend this blog and this exercise progression enough; I refer many of the postpartum patients I work with to this website and article for guidance. Thank you Dustienne!

Thank you so much Sarah! Your patients are so lucky to be able to work with you!