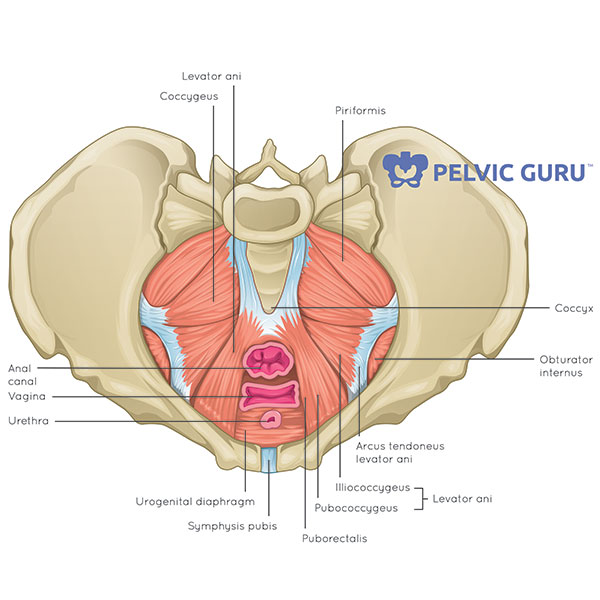

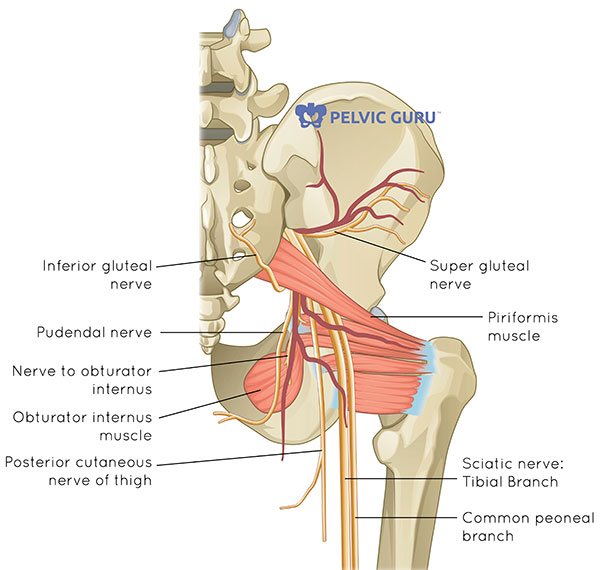

When we refer to the pelvic floor, it is often a shortcut to refer to the muscles that make up the pelvic basin. The pelvic floor also includes:

- blood vessels

- nerves

- ligaments

- fascia

- fatty tissue

- lymph

- skin

This is all within the border of the pelvis.

Illustration courtesy of Pelvic Guru. Used with permission.

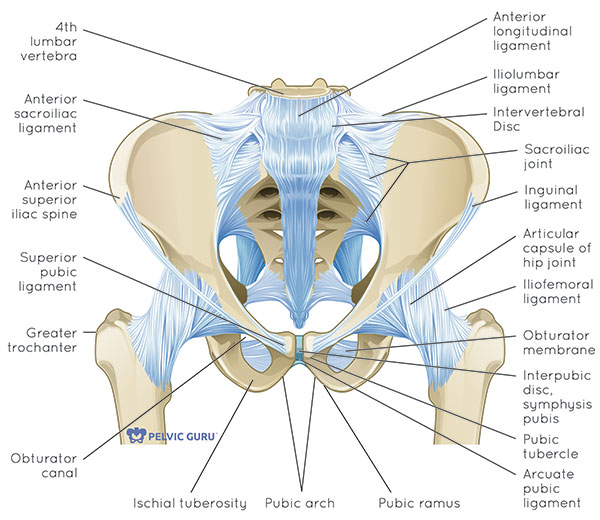

Bony landmarks of the pelvis

Illustration courtesy of Pelvic Guru. Used with permission.

We all have the bony ring of the pelvic girdle. There are two halves to the pelvis, called innominates, which are made up of three fused bones:

- pubis

- ilium

- ischium

Connecting these two pelvic halves in the back of the body are the sacrum (triangular bone at base of spine) and coccyx (tailbone).

There is a cartilage joint at the front of the pelvis that completes the pelvic ring called the pubic symphysis. This can get quite painful for some women during their pregnancy.

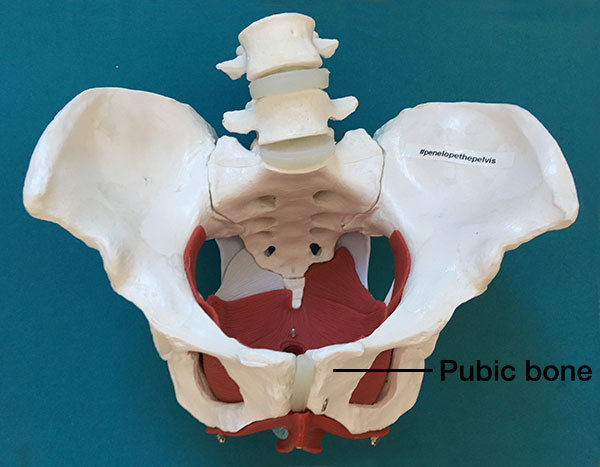

Where is the pelvic floor?

Let’s map out the area where your pelvic floor lives. If you are comfortable touching the bones that create the border as described above, please do. If not, just imagine where they are.

Find your pubic bone in the front of your pelvis.

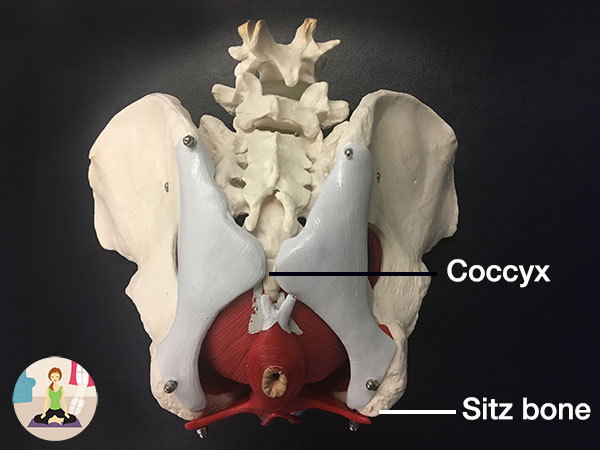

Reach around to the very bottom of your spine where your tailbone (or coccyx) is (hint: it’s usually lower than we may think).

If you are sitting, lift your right butt cheek and find your sitz bone (or ischial tuberosity).

You have now mapped out the diamond shape of the bottom of your pelvis. Within this bony border you will find all of your pelvic floor muscles!

The pelvic floor muscles are comprised of three layers.

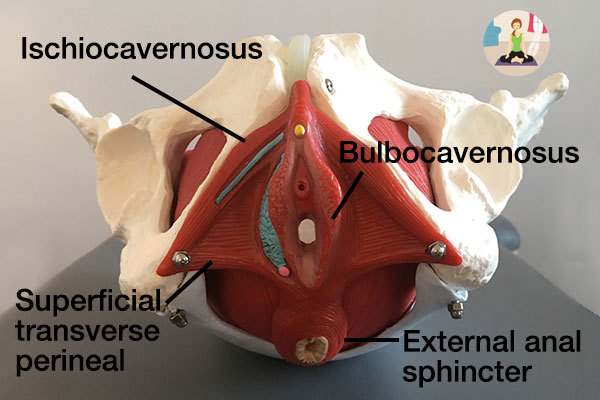

Layer 1

This layer is the outermost layer. This layer has four muscles that can be palpated both externally and internally.

These muscles can be palpated internally when one is a finger-knuckle-length in:

- Bulbocavernosus

- Ischiocavernosus

- Superficial transverse perineal

- External anal sphincter

This layer helps to close around all of the tubes at the end of the urinary system (urethra), reproductive system (vagina), and gastrointestinal system (anus).

Additionally, this layer allows for sexual function via clitoral and penis erection.

The tissue between the vagina and anus is called the perineal body. This tissue might suffer a tear during childbirth.

What’s different in the cis-male pelvis? Without the vaginal canal, they have fewer muscles and a differently shaped perineal body (called bulbospongiosus; the equivalent of the bulbocavernosus in the cis-female).

Also, the upside down V of the pubic rami (the bone of the pelvis) is more shallow because they don’t need to push a little human out of the pelvic outlet.

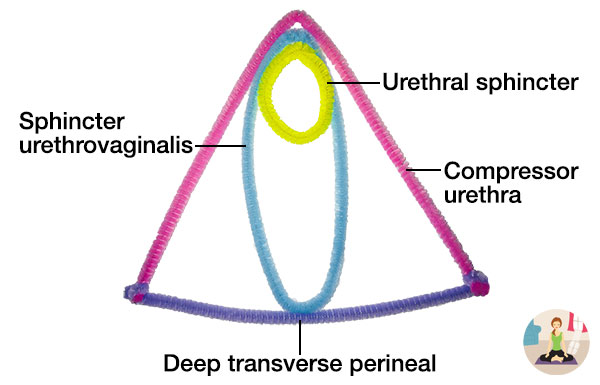

Layer 2

The closure around the tubes continues with layer 2. This layer is referred to as the deep perineal pouch.

It’s less obvious to pinpoint where the muscles are as compared the first and third layers, but for women with urinary urgency you can trigger this sensation when you palpate the compressor urethra.

This layer is palpated when your finger is two knuckles in. The muscles are:

- Urethral sphincter

- Deep transverse perineal

- Compressor urethra (cis-women only)

- Sphincter urethrovaginalis (cis-women only)

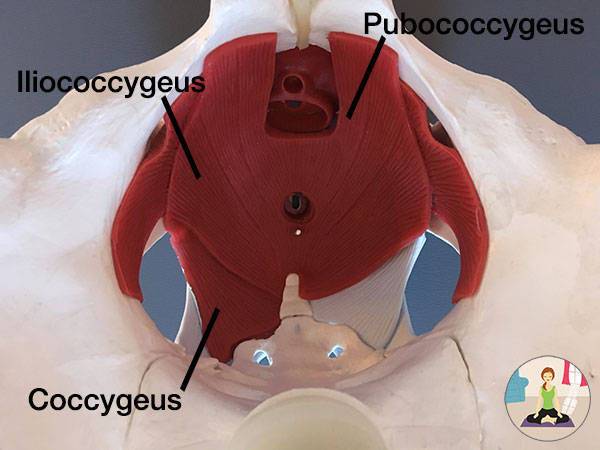

Layer 3

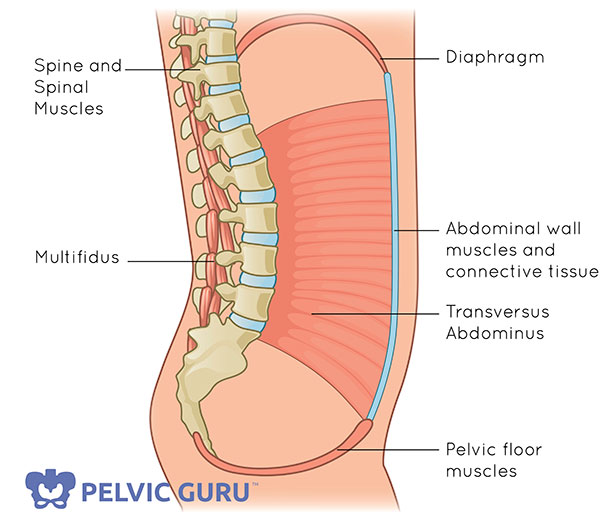

This layer is the innermost layer of the pelvic floor muscles. This layer is also referred to as the pelvic diaphragm.

This muscular sling looks like a hammock, acting to provide support for the bladder, rectum, and for those who have one, a uterus.

This layer has a right and left side:

- Pubococcygeus

- Iliococcygeus

- Coccygeus

The pubcoccygeus can be further divided into pubovaginalis (in cis-women) and puborectalis. Puborectalis has had some press thanks to Squatty Potty’s silly and anatomically accurate commercial.

This layer is important to hold the organs up. You can read more about the pelvic organs in this blog about pelvic organ prolapse.

We have more bony support in the front of the pelvis than in the back of the pelvis. Our little tailbone can’t support the uterus and bladder.

This is why sitting posture plays a role in preventing urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse. When we sit on our sitz bones, rather than sitting behind in a slumped posture, we are optimizing our pelvic floor function without even trying.

Slumped sitting

Neutral sitting

This layer also plays a role in our spinal health. A fancy word for core control is “lumbopelvic stabilization.” This layer of pelvic floor muscles coordinates with the deepest layer of abdominal muscles to control the spine.

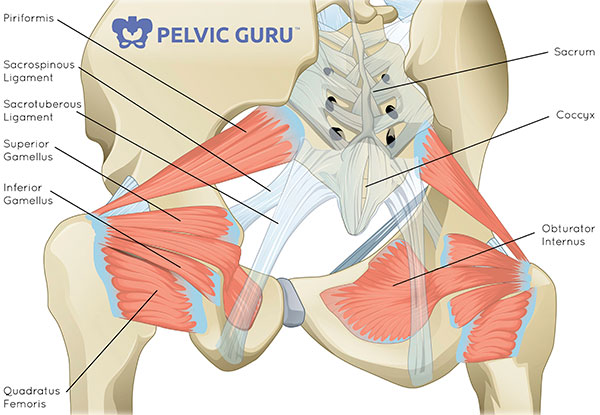

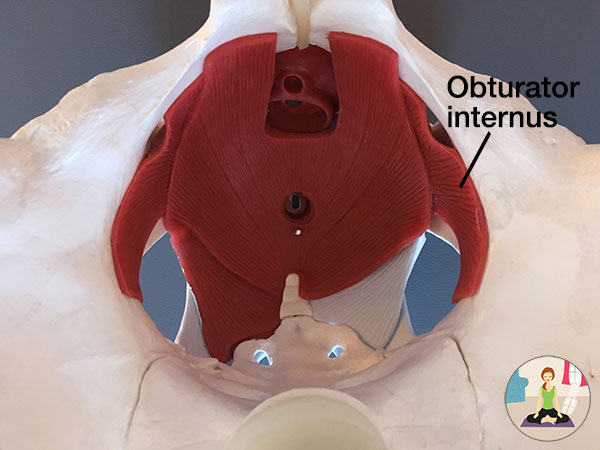

Pelvic wall muscles

Illustration courtesy of Pelvic Guru. Used with permission.

Not to be ignored are two important muscles that make up the pelvic walls: the piriformis and obturator internus.

The piriformis muscle is a hip external rotator (think turned out like a ballet dancer). It often gets press for causing pain in the sciatic nerve when it’s overactive or tight, but the problem could be with the obturator internus, which is also a hip external rotator. (The pelvic specialists reading this now have a magical glow about them. We love this muscle.)

The obturator internus is very often a culprit in deep vaginal, rectal or hip pain. Pelvic specialists love this muscle because when we palpate it, the patient will often say, “Yes, that’s exactly my pain. No one has been able to find that before.”

Illustration courtesy of Pelvic Guru. Used with permission.

So, if you experience what you think is sciatica, it might actually be your obturator internus irritating your sciatic nerve, not the piriformis. The sciatic nerve is the cream in the Oreo cookie between the piriformis and the obturator internus and can be irritated by either muscle.

Lengthen and strengthen: action steps for pelvic pain and incontinence

What do we focus on with our pelvic floor when we experience pain or incontinence?

If you experience any type of pelvic pain, you will want to release muscle holding, tightness, and spasm in the pelvic floor. This is called “downtraining” because we are looking to encourage the sympathetic nervous system (fight or flight) to downregulate and ask the pelvic floor muscles to relax and lengthen.

If your goal is to decrease urinary or fecal leakage, reduce or prevent pelvic organ prolapse, decrease back or hip pain, or optimize core control, you will want to strengthen the pelvic floor. This is called “uptraining,” which means we are encouraging the pelvic floor muscles to strengthen so they can engage along with the rest of the core musculature.

Downtraining pelvic floor muscles

When we look at releasing tension and lengthening the pelvic floor muscles we have a lot of tools in our toolbox.

Awareness

Now that you understand where the pelvic floor is and what it does, you can start to build more awareness.

Notice during the day if you find yourself holding during stressful moments. Notice if you find yourself holding while you are trying to elongate during a bowel movement.

Most of my patients find it helpful to reference this breath cues sheet to practice releasing tension during the day and incorporate it into movement, stretching, or a yoga home program.

Pelvic health physical or occupational therapy

It’s important to visit a primary care provider, urologist, gynecologist or urogynecologist first to make sure there isn’t a non-musculoskeletal cause of your symptoms. After you are cleared, you can see a pelvic health physical therapist (PT) or occupational therapist (OT).

Your pelvic rehab therapist will assess for:

- strength, weakness or over-activity of musculature

- flexibility and tissue pliability

- movement impairments and retrain for optimal neuromuscular coordination and control

- myofascial and visceral restrictions

To read more about what physical therapy can do for you, check out this page. For listings of pelvic health PTs and OTs near you, visit Herman & Wallace and APTA.

Dilator training

I wrote a blog on how you can use mindfulness while working with dilators.

This helps reprogram the brain from assuming the pelvic floor is a dangerous zone. Even if you are “relaxed,” the unconscious brain might try and protect you if there was previous pain in this region by creating tension in the muscles.

There is a free guided meditation at the end of this blog too!

Yoga and breathwork

Illustration courtesy of Pelvic Guru. Used with permission.

I’m linking these strategies together because they all have one thing in common: you!

You don’t need your PT or OT. You don’t need a piece of equipment. You have everything within you!

Your diaphragm has a direct relationship with your pelvic floor muscles. We can use breath and mindfulness to influence the nervous system and pelvic floor.

You’ll find lots of postures on my website you can explore, and also read more about pranayama, or breathwork.

Uptraining the pelvic floor muscles

Once you are feeling better and have less pain, you might start to work carefully to strengthen. Talk to your therapist about how to best approach that plan!

For those of you who aren’t recovering from pain and are looking to strengthen your pelvic floor muscles, you may want to explore Kegels.

There are three phases of rehab I think of when I’m helping guide someone to get stronger in the pelvic floor:

Awareness

Learning where and how the pelvic floor muscles are is the first step in strengthening.

Building awareness through education, like looking at pelvic models (shout-out to #penelopethepelvis) and anatomy photos, will help you find the muscles.

Other ways to build awareness is through observation of contractions while looking in a hand mirror, palpation of the muscles while practicing contractions, and biofeedback (external or internal sensor).

Isolation

In regards to training the pelvic floor muscle, I think of it in three steps:

- create awareness of where they are

- contract them without contracting other muscles (isolate)

- integrate into function

Now that you have created awareness about where the muscles are, you can learn to contract them without contracting the other muscles around them. This is isolating the muscle, as opposed to allowing the gluts or inner thighs to help out. Interested in learning how to contract your pelvic floor muscles with different cuing? Be sure to read this blog.

Functional training

In this phase of training we add pelvic floor muscle cues and contractions to movements. The Chair Pose is one example:

Start in Mountain Pose. Inhale, and descend into a half squat. This is Chair Pose. Exhale, and pull your pelvic floor up and in as you return to Mountain Pose.

If you are looking to uptrain and strengthen your pelvic floor, Optimizing Bladder Control is your go-to video.

Want to dive deeper? Check out the yoga video 4-pack.

“I have found when I create space for a home yoga practice, I feel better for a few reasons. One, I have a strategy for when things start to tighten up. Two, I know I am doing something to help myself, which helps me feel like I’m more in control of my life.”

Upon finishing the workouts, I feel more relaxed, more open/nimble, and I have a sense of control over my symptoms.

When I do yoga, I notice that my pain is reduced, bloating decreases, and I am more relaxed and accepting of the pain.